Movies from the Closet 🌈

The films that should've outed Joshua Taylor to his parents—plus, Bryden Doyle brings our latest T.O. Rep Rec: Dumpster Raccoon's screening of Querelle

Save The Date: Issue 10 Launch Party

July 25 ◦ 7:00pm

Join us for an evening of readings and games to celebrate the launch of Issue 10: Ten! Mark your calendars and stay tuned for the location and lineup reveal 😈

Movies from the Closet

The films that should have outed me to my parents

by Joshua Taylor

On a Tuesday evening in late-Autumn, the last stragglers have just arrived at the vicarage for their weekly bible study group. Conscious not to delay the communal acts of exegesis any further—it is already creeping past the agreed-upon start time of 7:30pm—they decline the offer of rooibos tea and chocolate Hobnobs from the vicar's wife.

The usual suspects are already there: Aideen with funny stories about her dad; Ian with a slew of complaints about work; Donald with the lawnmower slurps of his coffee that make his presence permanently audible.

And the vicar's son (me), giving a performance of “Humuhumunukunukuapua’a” from High School Musical 2. In the middle of the room. For the seventh week running.

The apotheotic altar of camp known as Sharpay Evans was where I conducted my own kind of worship, gleefully delaying the members of my dad’s congregation from theirs. So important was my innate homosexual delight in a song about a Hawaiian fish that I begged to stay up late every week to perform to the unassuming crowd gathered in my front room. Their entirely beige reaction never deflated my enthusiasm.

You can imagine my disbelief fifteen years later when my parents were surprised that I came out as gay. Their shock felt like an admission of neglect. To be surprised was to have experienced me differently, in a way that went beyond the usual differences between first and third person perceptions. It was to have cardinally misunderstood.

Had they not been paying attention? What had they seen in me if not someone diligently ticking off every facet of the gay stereotype? And while, of course, stereotypes are damaging, reductive, and crafted in oppressive contexts, my parents are not progressive enough to ignore them. I can only presume it was the holy veil of divinely enforced heterosexuality shrouding the vicarage that stopped my parents from noticing my childhood taste in film was as gay as a pantomime dame.

Perhaps the most egregious example of this is Spice World. Egregious because I have no memory of ever watching it. Details of my younger self’s glee at girl power have been parsed from my family’s oral history. Mum remembers this phase of my life most vividly, the soundwaves of endless zig-ah-zig-ahs etched deep into her skull by my compulsive viewing. At Christmases with cousins or pub lunches with friends, my parents never missed an opportunity to paint lively images of my toddler hips swinging and chubby arms flailing in attempted unison with Baby Spice (apparently my favourite; this seems unlikely as she is my least favourite these days but, as I say, I cannot remember). The story would always rise to a giggling crescendo about my early attempts at singing: I had the vocal cadence of a kangaroo, latching on with full screamish volume to the odd word I recognized then mumbling through the rest.

But being so young, my parents had little reason to suppose watching a musical comedy at least once a day for a year of my life was a post-natal indicator of homosexuality. Gerri’s Union Jack dress was little more than blotches of colour on a screen to a three-year-old boy.

As I grew older, however, my parents’ oversight became less easy to justify. Faces on the TV became memorable as “Anne Hathaway” or “Hilary Duff,” and my compulsive viewing habits fell under an incredibly predictable category.

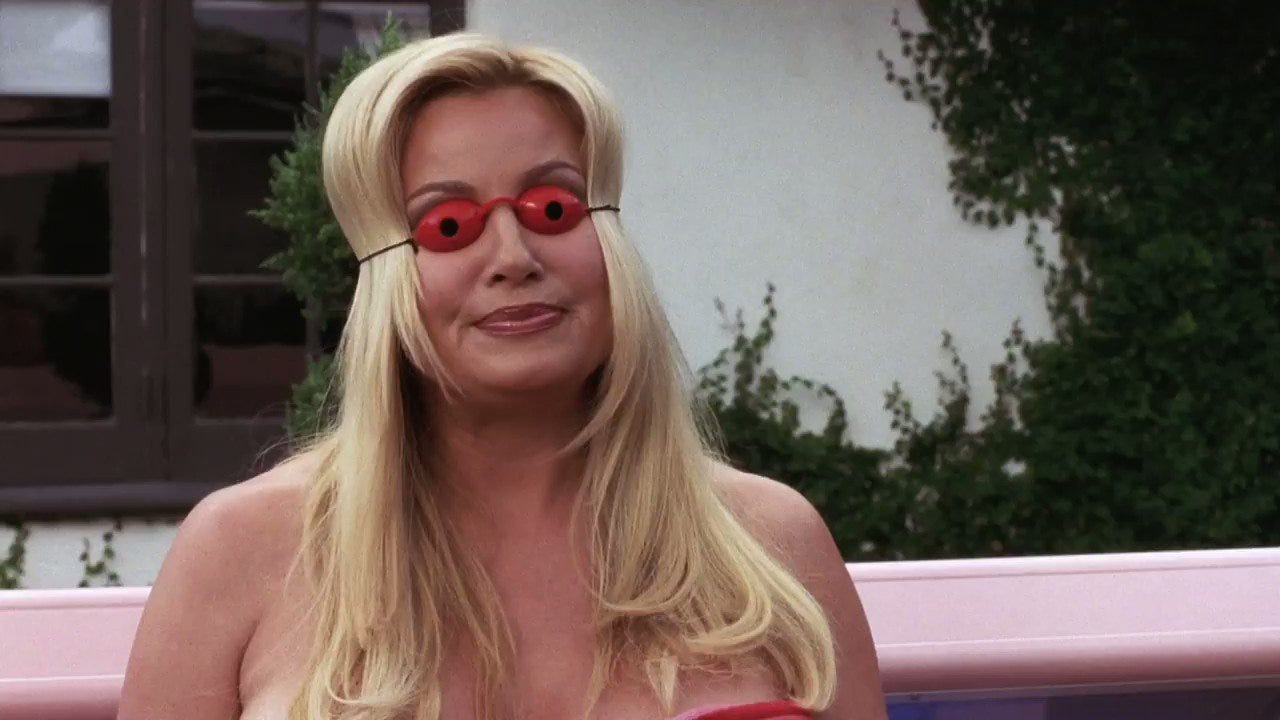

Like many other queer men of my generation, an entire decade of films marketed at our older sisters came to have a foundational influence on my personality. Maybe my parents thought my obsessive quoting of Jennifer Coolidge from A Cinderella Story was because I had a thing for MILFs? Or that I made notes on Julie Andrews’ lessons in etiquette in Princess Diaries because I dreamed of becoming a minor royal? Either way, as chick flicks came to characterize my puberty, plausible deniability that I was the kind of thing Thatcher sought to shield kids from with Section 28 became thinner than filo.

It goes without saying that the cornerstone of my gay indoctrination was Lindsay Lohan’s oeuvre. Screaming “Make good choices!” at the school gate to my parents or doing impressions of Gretchen at the dinner table are particularly fond memories. “Too gay to function” has since become not so much a part of my vocabulary as a Messianic standard which I strive to achieve.

Don't get me wrong, my tastes were not monolithically limp-wristed. Some films could have gone either way. The laddish charm of Benjamin Barry in How To Lose A Guy In 10 Days certainly could have been a formative influence on my heterosexual flirting abilities. I imagine my parents discussing with suppressed pride their hopes that one day I too could emulate the noughties romcom masculinity (which now feels staler than that bread they found in the pyramids, or centrism) of Matthew McConaughey. In reality, I only ever watched the film for the “You’re So Vain” scene, a long-winded route to getting my Carly Simon karaoke fix.

A few obsessions even look actively straight on their surface. Films predicated on violence, full of men who spit blood for a laugh and shit on each other for sport, are hardly going to feature in a Buzzfeed “If you watched these, you’re queer!” list. But underneath the facade of calloused hands and nose bleeds there was always an It Boy in various stages of undress (Brad Pitt in Troy, Heath Ledger in A Knight’s Tale) for tween me to drool over.

It goes without saying that not every child who grew up poring over these films is now LGBTQ+. But consider this an invocation to parents: know thy camp media. It is better to be prepared for a coming out that never happens than to find yourself asking ridiculous things like: “How were we supposed to know that performing ‘Humuhumunukunukuapua’a’ for the bible study group meant you’re gay?”

Joshua Taylor is a writer based in London who writes on fashion, culture, and anything queer.

T.O. REP REC: Dumpster Raccoon 🦝

by Bryden Doyle

How are Flash Gordon (1980), Barbarella (1968), and Phantom of the Paradise (1974) all connected? They were the first three films that Anthony Oliveira screened at Toronto’s Revue Cinema back in 2018 when he started his Dumpster Raccoon Cinema series. With this series, Oliveira sets out to reclaim maligned films so that he can share them with audiences. Oliveira explains, “It’s a space for our audience, with a queer sensibility, to reassess the detritus of pop culture with like-minded perverts and weirdos.”

Oliveira’s screening selections vary in terms of genre, era, and subject matter. He says, “They share in common only a sense, somehow, of failure that is the peculiar quality of camp—the ludicrously tragic and/or the tragically ludicrous.” Some of Oliveira’s favourite Dumpster Raccoon events include a screening of the Wachowskis’ Speed Racer (2008), a double feature of Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever (1995) and Batman & Robin (1997), and a showing of Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) that was accompanied by a cabaret (“I think some people fainted!” Oliveira remarks on the latter event).

Although Oliveira cites problems with Toronto’s film scene—“Our venues and our funding have disappeared, and our culture in general has become amnesiac about the past,” he laments—he still holds hope for it. With Dumpster Raccoon, Oliveira’s curation is an alternative to streaming services churning out algorithmic recommendations. He also sees value in people seeing films together in a theatre: “Dumpster Raccoon is a community first and foremost; art is, always, principally the occasion for the polis to assemble, and articulate itself. I want to see more of that—a return of the audience as a site of meaning-making and community-building.”

If you’re looking for queer films to watch with an audience for this year’s Pride month, why not try Dumpster Raccoon’s upcoming screening of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Querelle, based on Jean Genet’s 1947 novel Querelle of Brest? Released in America in 1983 after Fassbinder’s death, Querelle received mixed reviews and was nominated for two Razzie Awards for Worst “Original” Song. It follows its titular sailor (Brad Davis) as he reconnects with his estranged brother Robert (Hanno Pöschl, who also plays construction worker Gil), smuggles drugs, has sex with men and women, and evades police capture for a murder that he has committed.

Fassbinder’s characters are unable or unwilling to embrace their true selves: as they slip in and out of multi-coloured alleyways, it looks as if they are moving between different worlds, and between different versions of themselves while exploring their desires. The narrative thread of the police investigation functions as a metaphor for the fear of being outed. A threat of violence looms over the film, yet there is also a sensual quality to the visuals, with its close-ups of sweaty chests, shots of glistening spit, and hazy colours that make the settings swelter. Querelle’s muggy atmosphere will likely be complimented by the weather when it screens at The Revue on June 21st at 9:30pm.

🎥 Follow Dumpster Raccoon programmer Anthony Oliveira on Instagram

Bryden Doyle currently co-hosts the film podcast Almost Major, and has written film reviews for Inside Halton.com, as well as York University’s The Excalibur and Artichoke Magazine.

In the mood for something more?

Dive into the juicy archives of our newsletter and our online magazine.

Wondering what to watch?

Choose a mood on our Film Recommendation Generator and get a curated pick from writers, filmmakers, and poets.

Support us!

If you’d like to donate to our mag, here’s our PayPal! We’re volunteer-run, and donations go directly to our contributor honorariums and operating costs.