#11: Are You Still Watching? Dia VanGunten on The Idol

Fetishes, rat tails, and cults—plus: revisiting Paul Schrader's The Canyons, 10 years later

Dia thought The Idol was a joke... until it got her by the throat.

Fetish

by Dia VanGunten

“My Grandmother always said ya never trust a dude with a rat tail.” (Desiree)

The Idol’s opening shot is a voyeuristic close up of a woman in her feels. Offscreen, a photog demands a new emotion, another and the next, until tears fill her doe eyes and stream down her cheeks. Jocelyn (Lily-Rose Depp) wears a backless robe—an open window. The demonic garment was inspired by a Slim Aarons photograph of Marilyn Monroe and our “evil eye” recalls the icon, naked and dead in a hotel bed. As viewers, we’re voyeurs. The Idol puts us in a black hole—the retina—and staggered shots create a roving effect. Director Sam Levinson built a maze of false doors and trick mirrors. The Idol takes our inventory, pushes our buttons, and leads us into liminal spaces. But first, we feel superior, which is easy enough because The Idol is a hot mess. Skinemax x Häxan x Entourage x Children of the Corn x RENT x Baz Luhrmann.

I watched with armed disdain, one eye on TikTok, cracking occasional Skinemax quips. In my defense, it’s hard to accept The Weeknd as a dom so cult-daddy is a stretch. I ought to know better. I was born on a commune and, like most communes, it was more of a cult. Beauty and intellect aren’t crucial qualities in a leader. Gurus are just magnetic grifters. I retract my criticism of The Weeknd (aka Abel Makkonen Tesfaye). He plays a great clay figure. He’s the perfect good luck garden gnome; Priapus or Tanuki; soft-faced and tubby, with a rat tail.

Jocelyn is a trapped animal and Depp’s rear end delivers a nuanced performance. While shooting the music video, her flesh is sensual, until she repeatedly mounts the stage, no steps. Rump up. She clambers on all fours, exposed in a skimpy outfit, but she’s dressed for display. Blistered feet bleed into strappy stilettos and there’s an element of the grotesque, a nod to David Lynch whose work is marked by unsettling nudity. (Blue Velvet’s Isabella Rossellini is the trespassed body, inspired by the flayed carcass in a Francis Bacon painting.)

“People keep telling me I’m only human, as if I’m not.” (Jocelyn)

Basic Instinct plays on TV—dropping the term “suspension of disbelief”—and Jocelyn dons the red silk robe. Sharon Stone’s Catherine Tramell is sardonic, ice cold, and we aren’t sure what she’s capable of. Is she the dangerous woman she’s warning against? Jocelyn adds thigh-high stockings and heels. (“I want to be taller than him.”) She admires her reflection and smokes a cigarette. Tedros waits downstairs, nerves ratcheting. When she descends, he calls her an angel.

The Idol is Sam Levinson’s love letter to ‘90s noir, when psychological horror replaced gore. Morality decried splatter—too many dead cheerleaders—so studios revisited ‘60s-style psychosexuality. Jocelyn, titular teen idol, is that dead cheerleader. She’s Britney/Ariana/Miley. (Even this summer’s special edition of Taylor Swift: Breaking Bad Boy.)

She’s traded personhood for stardom. She has no agency and no right to privacy, pain, or desire. She’s a commodity. Symbol. Vessel. Potential. No wonder she wants Tedros to possess her. He relieves her of the evil eye: wrapping her head in red silk, making her a faceless totem.

“Jocelyn is actually in quite a vulnerable position for all the power and privilege that she has.” (Intimacy coordinator)

Jocelyn seems the perfect victim, except that she’s defended by fame, surrounded by servants and insulated by loved ones. Everyone is concerned: handlers, managers, agents and producers, even the maids convene in whispers. A prior hospitalization is hush hush. Jocelyn puts a lot of pressure on herself. She wants to be like Prince—immortal. She seems to think that Tedros can make this happen, even though he’s basically a nobody. Nonetheless, he delivers. For starters, his followers are future stars. Tedros has an eye for talent—and for pain. He’s Peter Pan and the lost children, drugging, screwing and singing in the panty-less lap of luXXXury, like a corrupted Partridge Family. It’s good fun if Jocelyn can afford it, but the Moneymen say she’s running out of money. Star-makers claim she’s losing momentum. She’s at a crossroads: make it or break it.

Tedros attracts Kanye’s producer, Mike Dean, and then, during the recording session, he blindfolds Jocelyn and pleasures her while she lays the track. Mike Dean laughs, grimaces and fidgets. A crowded room exchanges wary looks. No one can agree on what exactly they’re seeing, because kink is cool, but not when consent is blurred by abuse. Tedros tortures his followers with shock collars, threatens the Valentino attendant and strikes her personal chef.

That last one sucker punched me. It sent me reeling—back to my mother’s kitchen, when I overlooked a similar violence. I was only 15 and my ex had a ponytail, not a rat tail, let’s be clear, but just like Jocelyn, I dispatched the injured party. Now The Idol had my full attention.

“That’s my family, oh, we don’t like each other very much.” (The cult singers)

While his kinky methods are effective, they take a toll on Tedros. Jocelyn blossoms and his followers explore their potential, but he’s a goblin with receding glow. He devolves into envy and violence. I missed this ominous note of horror—Succubus myths escaped me, and biblical Samson. All that cocaine was a red herring.

The Idol’s cult-meets-showbiz storyline was influenced by Charles Manson, whose music is quite good, if the listener can separate art from the artist. Tedros targets Jocelyn for her industry connections. (Manson chose Sharon Tate’s address because he believed the home was occupied by a music exec.) Tedros appropriates Jocelyn’s property and separates her from her support system. (So too, Manson and Dennis Wilson of Beach Boys fame.) We know Manson inspired The Idol because the characters say so. Her entourage serves as a Greek chorus, so we hope “the team” will ride to the rescue and sure enough, they show up in a battalion of expensive automobiles, but their professionalism dissolves into depravity when they see the profitability of Tedros’ star stable.

“Cult,” like the word “idol,” is ascribed with the “other,” but it’s easy to wind up in a cult. I was born into one. You too. Family functions as a cult and cults promise to deliver on the myth of “family.” Estranged from their families of origin, the followers look to Tedros as de facto father figure. They’re chasing two dreams—stardom and family.

Jocelyn’s affection for Tedros seems boundless, until she invites an ex over for a loud sex sesh, leaving Tedros to bang on the locked door. He is going to KILL her. The next time we see him, he’s a haunted soul. He’s disheveled and greasy with a toxic ooze. We imagine pools of blood, words scrawled on the wall… what has he done to Jocelyn? But she wakes up chipper and in charge, ready to face off with Tedros and claim his cult for herself. “These are my people now,” she declares. Jocelyn rallies the talent and summons her team. She puts on a show for the record label and has Tedros arrested. Are we relieved to see her alive, or are we disappointed?

“You are never gonna meet a girl like Jocelyn. She’s not walking down the street, she didn’t go to your high school, she’s not working at the diner, and she did not marry your best friend.” (Nikki, music exec)

Months later, we reunite with Jocelyn at an arena, on the first night of her already blockbuster new tour. Carried through a series of maze-like passages on a golf cart, she’s angelic in white (her head shrouded by an Alexander McQueen scarf, blood red, with copulating skeletons). Tedros is outside in an expansive parking lot. The devil’s at the crossroads but he can’t collect any souls. Although Jocelyn does him the courtesy of leaving an artist’s pass at the box office.

They reunite in her dressing room, where Tedros spots the hair brush from Jocelyn’s abusive childhood, realizing that it’s brand new. He is shook. The golf cart arrives and they ride together through the liminal-nausea of the massive stadium, which is extra creepy because this episode was shot at an active venue, during The Weeknd’s tour. Joselyn sweeps on stage—open arms, a marble urn—and 70,000 real-life Weeknd fans cheer his character’s humiliation.

Jocelyn introduces Tedros, kisses him possessively and points to the sidelines. “You’re mine, forever,” she says. “Now go stand over there.” She glitters in the bright lights, the crowd roars, and we realize that Jocelyn is not the victim, the would-be Sharon Tate or exploited Britney. We finally see her for what she really is—THE UNCANNY OBJECT... THE ENCHANTED AMULET... THE FETISH.

Dia VanGunten exists in a liminal space as an adherent of the mythic trickster and the lunatic behind the existentialist horror series, Pink Zombie Rose (comics about undead psychonauts). While we didn’t need a second season of The Idol, Dia hopes we go full-on femme-dom.

For the 10-year anniversary of Paul Schrader’s The Canyons, revisit this feature from our back issue…

A Cold Deadness: In Praise of The Canyons

by Will Sloan

Recently I found myself watching Paul Schrader’s The Canyons (2013) for the fourth time, hoping to finally like it. I first saw it during its initial release in the summer of 2013 when it opened simultaneously in theatres and online—a novelty at the time. I opted for the theatrical experience, out of respect for the legendary writer of Taxi Driver (1976) and director of Blue Collar (1978). I knew the Tomatometer was stalled at 21%, but I sat there watching it with the stoicism of Buddha, certain that Schrader must have made it this way on purpose. I finally gave up about 15 minutes before the end and joined the rest of the audience in laughing. There was no way around it—this was a bad movie. I also disliked it on two subsequent viewings. This time around, I’m uncertain if my opinion has changed. I do know I will eventually watch it a fifth time. Maybe that means I’ve come to appreciate it as… something. I’m not sure what. A conceptual art project? A documentary on its own making? A vibe?

One thing I know for sure about The Canyons is that whole eras have come and gone since my first viewing of it eight years ago. To 2013 audiences, the big draw was Lindsay Lohan, whose behind-the-scenes behaviour was chronicled in a much-discussed New York Times article called “Here Is What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan In Your Movie,” and cannily exploited by the filmmakers as a marketing tool. At the time, her trajectory from Disney princess to cautionary tale was still an ongoing media drama. Poor girl—she can’t even get it together for a trashy, Kickstarter-funded erotic thriller co-starring a porn star. Nowadays, all of this is fairly distant in the popular memory… although now that the discourse surrounding addiction and mental health has evolved so dramatically, Lohan’s story is probably due for a relitigation.

Read the rest →

Feeling Incandescent? Myrna Moretti recommends Electric Dreams (1984)

dir. Steve Barron

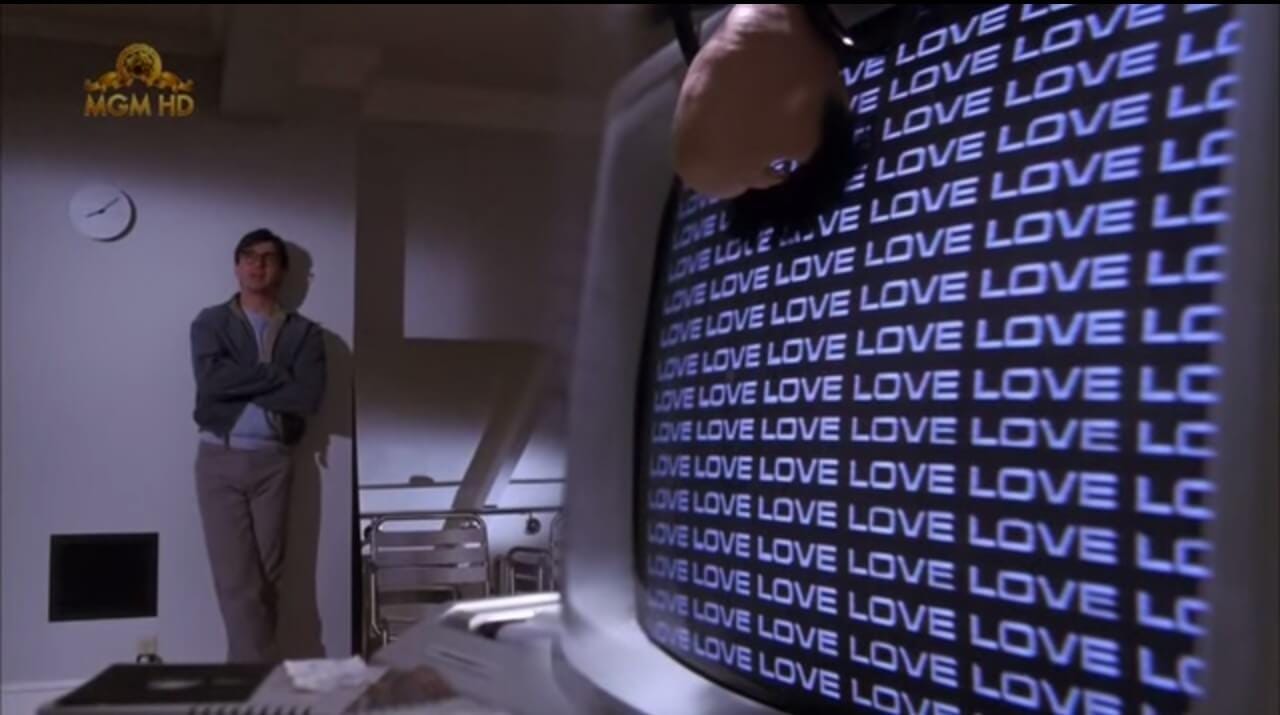

Part Tron, part 500 Days of Summer, Electric Dreams is a strange, sweet 80s computer romance. The film is a San Francisco set Cyrano de Bergerac style story. Lead character Miles (Lenny Von Dohlen, who you might recognize as Harold from Twin Peaks) purchases a computer to help get his life in order. When a beautiful woman moves in upstairs (Virginia Madsen), he uses the computer to create music that will woo her. That’s right, not seduce her, but actually romance her. But then the computer, Edgar (voiced by Harold and Maude’s Bud Cort), falls in love with Madeleine too.

As soon as this triangle was established, I expected the film to get very dystopian, but it doesn’t. Instead what we get are numerous sequences backed by Giorgio Moroder’s perfect soundtrack showing the computer’s imagined possibilities (this is the year of the “1984” Mac ad after all) and showing Miles and Madeleine visiting Alcatraz and a fairground on their first date. I associate the word incandescent with a kind of ephemeral electric shimmering energy. The soundtrack alone has that, with its pop-y, electronic score—I assume Daft Punk loves this album. But what’s really incandescent here, is the highly imaginative, hyper dynamic ways that the filmmakers visualize the computer’s personality, musical talents, and its role in domestic tasks. Shots of 1980s computers abound! However, they also avoid the techno-anxiety that characterized so many other films of the same decade. This representation is truly an electric dream.

Myrna Moretti is a PhD candidate in screen cultures at Northwestern University and a documentarian.

Wondering what to watch?

Choose a mood on our Film Recommendation Generator and get a curated pick from writers, filmmakers, poets, and artists.

Donate

If you’d like to donate to our mag you can do so through our PayPal! We're volunteer-run, and donations go directly to the mag and contributor honorariums.