Are You Still Watching? 2024 Oscars Round-Up 🏆

In anticipation of Hollywood’s biggest night, In The Mood Magazine’s editors and contributors share their thoughts on every Best Picture nominee.

Whether we loved ‘em or hated ‘em, we watched all the Best Picture nominees so you don’t have to. Scroll down for our brutally honest thoughts on this year’s crop:

Poor Things

by Alex Mooney

As I ride the subway home from my second round of Poor Things, various hooks and sound-bites float through my head: “Yorgos goes nice-core,” “Barbie meets Frankenhooker,” “great gowns, beautiful gowns,” “a cast at once underused and at the top of their game,” “Robbie Ryan finally delivers a non-beige palette,” and so forth.

And yet:

The film contains some of The Greek’s most histrionic forms of violence (desecrated corpses, various “scientific” violations of living creatures, and the threat of genital mutilation for starters) at once more shocking for their disruption of a less oppressive mood and all the more distanced and dispassionate in their more casual framing

Lanthimos lacks the infectious buoyancy of Greta Gerwig’s money-printer (sadly he does not lack her tendency to gussy up platitudes) and the steadfast, aspirational commitment to one, and only one, sarcastic note that animates the Henenlotter corpse-comedy

What can I say—Dafoe made me tear up, Ruffalo made me giggle like a school-girl, and Stone made me nostalgic for the time in our lives when we get to figure out how our bodies work

And on multiple occasions, the look of the film becomes somewhat… puke-ish. Cinema is a land of contrasts, et cetera, et cetera.

It’s clear by now that Lanthimos is sanding some edges off of his style to be successful in Hollywood but I’m not convinced that’s a bad thing. It’s probably true that some of the film’s “commercial” appeal is thanks to television writer Tony McNamara, who wrote this and The Favourite, and seems remarkably well-suited to Lanthimos’ vacuum-sealed worlds*, but his next film, Kinds of Kindness (which reunites him with screenwriting partner-in-crime Efthimis Filippou but hosts a cast full of A-listers) might settle the “awards-chaser” debate once and for all.

*What makes Poor Things a step forward—as much as it’s also a step down—for Yorgos, is that he’s finally able to imagine what freedom from these spaces might look like

Not that there aren’t downsides: an audience surrogate (groan-worthy softboy Ramy Youssef) is a new addition to the Yorgos-verse, but a tacky and unnecessary one if you ask me.

In this sense The Favourite, which will likely remain his best for a long time, exists at the ideal midpoint in his career; he takes the characters’ emotions seriously, which pays devastating dividends when they start to ruin each other's lives. The characters in Poor Things are as pitiful and pitiless as the title might suggest, but it also happens to be a really funny movie, so I’m okay with that.

And what to make of this relatively mean-spirited movie’s textual throughline about overcoming a cruel former self? “Carve with compassion,” a mantra both undercut and reaffirmed the moment it’s uttered, captures the film’s contradictions so neatly I might as well stop yapping about them.

Alex Mooney is a Toronto-based writer, overworked student, and underworked bartender.

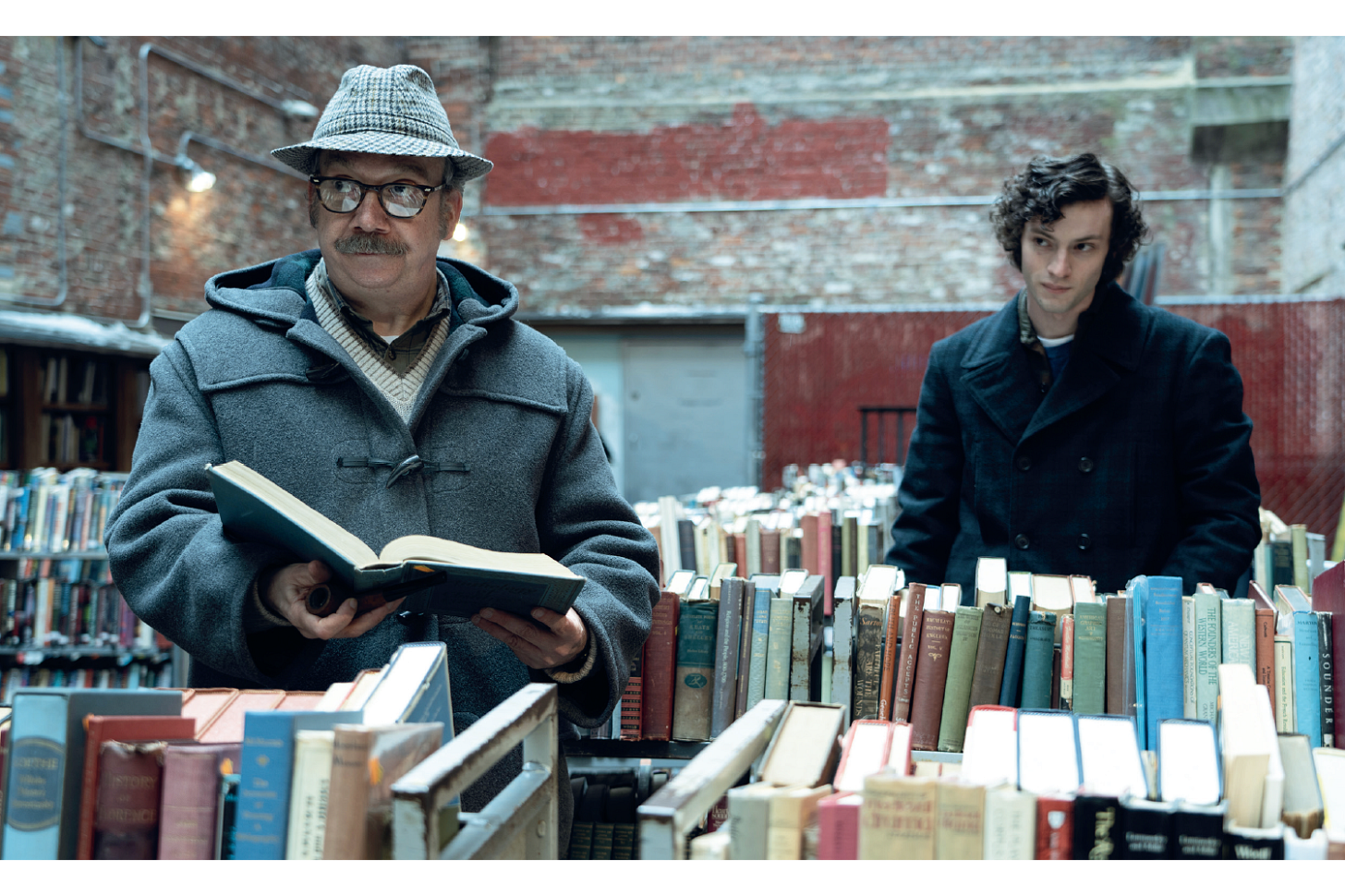

The Holdovers

by Winnie Wang

The entirety of my 2023 was spent enraptured by Avery Trufelman tracing the origins of preppy clothing on the podcast Articles of Interest. The transition from made-to-order to off-the-rack clothing accompanied me on crisp morning walks, the influence of streetwear on Tommy Hilfiger on trips to the grocery store, the popularity of vintage American styles in Japan on work commutes. My eBay search history became populated with variations of “ralph lauren oxford,” “j press rugby shirt,” and “vintage gap khakis.”

Between May and August, I embraced plenty of soft pastels, boat shoes, and billowy oxford shirts to survive the heat. The beginning of the year, though, was admittedly a struggle. How does one stay warm without looking too technical, après-ski, or Scandinavian? Dressing for the frigid temperatures of an East Coast winter was already hard enough without maintaining a collegiate appearance. But when September arrived with the promise of cold weather—and another opportunity to prove myself—around the corner, I found inspiration in Alexander Payne’s New England coming-of-age tale. The boys of Barton Academy wore ensembles with varied fabrics and textures: a grey wool blazer with a navy tie, a navy blazer with burgundy trousers, a brown corduroy suit with a red-blue striped tie. I studied, over multiple viewings, the hues of Angus Tully’s scratchy wool sweaters, the length of his too-cropped jeans, and his choice of outerwear. Shots of history classrooms and busy hallways were particularly instructive of the colour combinations at my disposal. Though this past winter flew by before I could acquire the appropriate pieces, I’m now equipped with new search terms for the next—third time’s the charm.

Winnie Wang is a writer based in Toronto.

Killers of the Flower Moon

by Will Sloan

Art is bad for inspiring change but good for helping us make sense of the moment. The many virtues of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon have been well dissected at this point, so I’ll limit myself to noting that it’s been a long time since I’ve seen a movie that so well identifies how evil functions on a day-to-day, human-scaled level.

A corrupt system doesn’t happen on its own. At the top, it is shaped by visionaries and idealogues like William King Hale (Robert De Niro). A wealthy and influential Oklahoma citizen, Hale is a public-facing friend and ally of the state’s oil-rich Osage Nation, while secretly masterminding a conspiracy to marry white settlers into wealthy Osage families, then murder the spouses for their land rights. Assisting Hale are a network of direct accomplices, and below them are the rest of us: the people who inhabit their world, and perhaps even materially benefit from it. We may recognize this system at work, and even object to it on moral grounds, but individually we have very little power to change it. It’s easy for us to sit back, absolve ourselves of responsibility, and perhaps even contribute in ways large and small to upholding it.

Hale’s nephew Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), the stupidest and most passive protagonist in a long line of stupid and/or passive Scorsese protagonists, is an accomplice who tells himself he’s a bystander, and even starts to believe it. His wife, Mollie (Lily Gladstone), understands that the world is against her and her family, but believes that Ernest is a good ally within this system. The film’s central mysteries are how he can directly contribute to her attempted murder while still believing himself a good and loving husband, and why she is unable to confront the truth until the very end. When you’re living in a world whose terms a man like Hale defines, believing his words of reassurance is a way to compartmentalize the pain. When he tells his nephew that, like it or not, Mollie is a goner, and all we can do now is ease her suffering, I was put in mind of that day a few weeks ago when all of the Canadian pundits and politicians posted some version of: “We are all but powerless to change what is happening in the Middle East. But we have so much power to hurt and harm each other here…”

Will Sloan is a writer and podcast mogul based in Toronto.

Past Lives

by Sennah Yee

When the family chooses their English names before immigrating to Toronto, Leonard Cohen’s “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” plays in the background—coincidentally, the song my dad would sing to me as a lullaby, and that we later chose for our dance together at my wedding. When my dad immigrated to Toronto at 5 years old, his school principal picked his English name, using the same first letter as his Chinese given name. When he was 30, he legally added it back.

I fear that the amount of well-intending white people who told me I’d love this set us up for failure. If you’re reading this: I’m sorry, and it’s okay.

Nora, her husband, and her childhood sweetheart all being open to hanging out together felt absurd to me—but maybe this says more about my own insecurities. In high school, I had gotten tickets to a Rihanna concert with someone I was seeing at the time. After she ended things amicably, she invited her new boyfriend to join us at the concert. All I remember is our lumpy grassy lawn seats, and how even Rihanna’s “Umbrella” routine couldn’t distract me from noticing my ex’s new boyfriend’s arm around her.

How Chinese I feel, look, act, depends on who I’m with. Sometimes it’s all I think about, other times I don’t think about it at all. Sometimes it’s magical—feeding what was once left to scrounge—other times it’s maddening, to be looked at, but not seen.

It’s not lost on me that Celine Song, Greta Lee, and I all have white screenwriter husbands. Celine’s husband’s name is clickable on Wikipedia, though he has no photo on his page. I gasp when I realize he’s the guy from that viral “Potion Seller” video. Greta’s husband, according to reputable sources People and Yahoo, “is active on social media, unlike Lee” and “posts frequently about his wife.” My husband has posted a total of 11 times on Instagram since 2018. His posts include a bowl of ramen (so he could get a free dessert at the restaurant), our large tabby cat, and wishing me a happy birthday.

Sennah Yee is the author of How Do I Look? and My Day With Gong Gong.

Anatomy of a Fall

by Quinn Henderson

One of the most fun Oscar season activities—besides watching movies and complaining—is playing pop sociologist and formulating a cultural diagnosis from Best Picture nominees. Looking at the slate of low-middle- to middle-high-brow productions, I ask questions like, “What does this say about what the Academy is looking for?” and “What is the broader cultural imagination craving?”Anatomy of a Fall gave me a lot of fat to chew on.

Its nomination cements the fact that the Academy’s taste is growing ever more aligned with that of a typical Cannes jury. Three of the last four Palme d’Or winners have been nominated for Best Picture (Anatomy, Parasite, and Triangle of Sadness were nominated; Titane, unsurprisingly, was not). The last streak like this happened between 1993 and 1996—when distributors like Miramax, Channel 4, and Working Title were pushing indie and arthouse sensibilities into the mainstream, and the purview of the average Oscar voter. But what makes this current trend so interesting is the recent crop of Palme noms are either entirely or partially non-English-language films. Previously, the only Palme Best Picture nom made outside specific Anglophone nations, the U.S., U.K., or Australia, was Michael Haneke’s Amour.

Part of this is likely due to the Academy’s push to expand its membership pool to represent more diverse voices, opening it up to voters more inclined to champion something a little left-of-centre (please do not mistake this for me giving any credit to the Academy). The fact that there are 10 Best Picture slots to fill these days doesn’t hurt either. This convergence might also be spurred by the—for lack of a kinder word—normie-fication of the Cannes jury: I mean, Greta Gerwig is the jury president for next year's fest. She’s a great filmmaker and all, but also, she just directed the most popular film of the year.

I also see Anatomy of a Fall’s success as evidence of society’s pent-up desire for a tried-and-true genre movie that doesn’t really get made anymore: the courtroom thriller. We’ve already seen ‘90s faves like Brendan Fraser and Blur stage comebacks after dormant slumbers, so why can’t this former titan of the box office (and the Oscars ceremony) return to prominence? Maybe interests have migrated to true crime shows, but I think there’s something special in having magnetic actors playing lawyers, victims, and suspects who love speechifying.

Anatomy doesn’t deliver the same hammy pleasures as its forebearers; or, perhaps more accurately, it packages them more prosaically. The film’s architecture is complex, its moral POV ambiguous, and whether or not Sandra Hüller killed her husband often seems beside the point. But make no mistake, at its core, this is pure popcorn fare. Take the climactic scene where the shaggy-haired, pre-pubescent moppet takes the stand to give his final heartfelt testimony. It’s a scene that feels right at home in the hypothetical ‘90s studio version of this film (directed by, let’s say, Gary Fleder, and starring Annette Bening), accompanied by a sonorous James Newton Howard orchestral score. The fact Anatomy plays the scene straight without music is just a minor superficial difference.

That said, to Anatomy’s credit, it is a far more accomplished film and has a lot more on its mind than your typical John Grisham potboiler—namely the necessary armistices that must be struck in every relationship or the concept of that all-too-malleable instinct called “certainty.” If there’s one thing I’m certain about after it, however, it’s that I desire to have hair like Swann Arlaud when I’m older.

Quinn Henderson is a writer based in Toronto. How original.

American Fiction

by Celia Mattison

Five responses to: “Hey, you work in book publishing? Have you seen American Fiction? What did you think?”

Yes, I did, because not only do I work in book publishing, but I am also a light-skinned woman from New England, and that meant when I saw the trailer I thought representation has gone too far. I do not share the compulsion so many people have with being “seen.” Never have I seen a stranger and thought, oh god, please perceive me.

I feel like a bad Black person because I really don’t like Jeffrey Wright’s acting. I find his head-bobbing incessant: every shot/reverse shot, he’s nodding his head in a different direction. He acts like a piece of clockwork, each line delivered with a Super Smash Bros. button-smash combination of head-tilt, gravel voice, eye-squint.

It reminded me of previous awards darling, CODA. I felt the same panicked revulsion when the film started and I realized I’d have to observe something hideously lit and poorly shot for two hours. Like getting a ride from a friend and opening the door to see that their car is completely disgusting.

I think for a Black movie to be good it needs to appeal to white people a little less. Come along for the ride, I guess, but stop demanding we stop at Cracker Barrel every exit. American Fiction is a movie about the limits of white taste built to appeal to white taste, which is why the Black women are pathetically thin caricatures and Adam Brody is onscreen so much. American Fiction feels like a can of soup watered down to stretch across too many meals so that the taste bears no resemblance to what the label promised. It’s not more food, it’s just more of nothing.

Nope, haven’t caught it yet.

Celia Mattison is a film critic and the author of Deeper Into Movies.

Barbie

by Cleo Sood

Hater Barbie: I’m a Barbie girl in a post-hype Barbie world. And that hype? Unwarranted!

On a sleepy night in mid-August, with one of my girlfriends and her boyfriend, I went out and watched Barbie. Afterwards, I felt similar to an angsty pre-teen receiving a toy doll—like, “This Barbie is lame.”—all while knowing deep down that I would’ve enjoyed it at an earlier time, with a different vibe. I would’ve enjoyed it more at an earlier time, like if I’d been boozy from brunch with a girl gang, whispering giggles to each other at an explosive opening weekend event. Instead, I was defending my Barbie bashing against my friend’s pro-Barbie straight-man boyfriend.

Multi-Level Marketing Barbie: This Barbie thinks your story was a feature-length Mattel advertisement. (And I am someone who quite literally collects dolls.)

Gerwig’s Barbie—with its cheeky charm and emotionally manipulative montages—bore more resemblance to one of those Dove soap self-esteem commercials than the compelling monomyth Gerwig is capable of à la the rest of her oeuvre.

Barbie tells an elderly woman, “You’re beautiful.” Moments later, Barbie is paralyzed by her flaws, her own perceived lack of beauty. She’s relatable and likeable in her insecurity. But Barbie would be close to Unabomber status—would be too complicated and unlikeable—if she were to look at a wrinkled world with its ozone depletion sunspots, its clogged corrupt pores, and confront human mortality with anything but whimsical awe.

Barbie can be depressed so long as she isn’t depressing.

It’s a little ironic because a well-intentioned critique of these gendered politics of likeability would’ve jived well with America Ferrera’s Oscar-securing monologue, but participation in these gendered politics jives better with the business of selling shit. Dolls. GM Cars. Soap. You name it.

And Gerwig isn’t afraid to sell shit—as evidenced by the billion-dollar (150 million to be precise) Barbie marketing campaign. What’s more, is that she does it well. It’s how she convinced Mattel of her script, It’s why the Barbie movie becomes the Ken show in its final act: people like sob stories, but they like gags better.

Notes on Noms From Oscar Barbie: Not Good Kenough?

_____ cemented his award-worthy comedic chops

Ryan Gosling’s performance as campy Ken

Ryan Gosling’s on-stage reaction to the Oscars’ La La Land error

If you say, “Margot Robbie should’ve received a Best Actress nomination for Barbie” three times into a mirror, Tonya Harding appears with a baton to do the job herself. #Whack

America Ferrera has given comfort and inspiration to the greatest girl minds of our generation. She’s allowed to shed Ugly Betty for conformity Barbie.

Gerwig also wasn’t nominated for Best Director the night Lady Bird won its Best Motion Picture Golden Globe. They hate to see a Greta Gerlboss win. 🏆🤷🏽♀️

Cleo Sood hates writing, but she loves having written.

Oppenheimer

by Adrian Murray

Oppenheimer has a catchphrase. It’s originally from the Bhagavad Gita, though I never knew that, I just knew it’s what Oppenheimer said after The Bomb went off. I assumed he came up with it on the spot. It’s like a karaoke song you didn’t know was a cover and instead was “as made famous by…”

If you Google the quote, the first hits are for Oppenheimer’s use of it. I always imagined him saying it with the same flat intonation as Neil Armstrong’s “one small step” quote, probably at a press conference surrounded by flashing bulbs and men with press signs in their fedoras. Or maybe I thought he mumbled it quietly while staring out at the mushroom cloud, then Einstein turned to him and asked, “What’s that?” and Oppy responded, “Nothing. Nothing at all.” Or sometimes I imagined it being something attributed to him by someone else who was there at the time. A co-worker who, when asked about it, said, “You know, Oppy said the craziest thing right after she blew…”

I didn’t know until today that there’s footage of him saying it. In a perfect black-and-white close-up, he avoids looking at the lens as he contextualizes the quote and why he thought of it, saying it mournfully as he dabs his eyes. The angle, the lighting, and the lack of setting make it feel like a self-tape that knocks it out of the park with a flawless performance. In the movie, Oppenheimer notes that the psychological effect of the bomb will be significant—the sight of the mushroom cloud and the knowledge that all this terror was done by one device will stir something in those who see it and hear about it. It’s a bigger bomb, a better bomb, a bomb recontextualized by its performance.

Oppenheimer’s catchphrase is an elephant in the room in a movie with a lot of elephants in a lot of rooms. In addition to a huge cast of A-listers as historical figures, we’ve got big historical moments to get to—obviously, we’re gonna see The Bomb going off. We’re also gonna see Oppenheimer saying his catchphrase, an actor who looks like Einstein, and Florence Pugh’s tits.

Biopics are plagued by expectations and can easily seem like historical karaoke. Can these historical moments be contextualized or recontextualized? My partner let me know that there’s a French euphemism for orgasm that translates to “little death.” Maybe this is why Nolan chose to recontextualize Oppenheimer’s catchphrase the way he did, by (spoilers ahead) combining it with Florence Pugh’s highly anticipated scene of “prolonged nudity.” In what seems to be the fantasy of a tenured professor, graduate student Florence Pugh rides Oppenheimer in his study as she demands he demonstrate how smart he is by translating ancient Sanskrit passages.

What could it mean? Oppy’s creative urges as destructive urges as sexual urges? Love as death? Explosion as orgasm? I initially dismissed it as too juvenile to read into—just a horny fantasy shoehorned into what wants to be a deeply serious movie. But then I questioned my own dismissal of fantasy in this context. Being horny and having sexual fantasies are deeply human experiences. We can work towards a fantasy, or try to avoid our fears. Our actions begin with our body and mind, and somewhere within Oppenheimer’s skin was the ability to make material the fantasy of the most destructive weapon the world has ever seen. He’s flesh, and so am I. If I wasn’t stirred by the movie, I was shaken by the thoughts it led me to. It’s the tackiest, least expected, and most interesting moment in the film. In the karaoke of recreating historical events, it’s a performance that gave me pause. The movie that is, on those tits.

Adrian Murray is a filmmaker based in Toronto.

Maestro

by Ethan Vestby

“Do I need to be watching this?”

The thought crossed my mind while watching Maestro on the evening of December 20th, 2023. I could’ve been watching anything, and like LITERALLY anything else—multiple streaming services, a bevvy of unwatched Blu-ray discs, not to mention my digital collection of films. When the entire history of cinema is available to you at a moment’s notice, it feels increasingly difficult to justify watching mediocre new films at home, other than to be in on some current discourse that will inevitably shift within a moment’s notice to whatever’s the new awards season or blockbuster film inspiring mockery or some form of outrage.

Did I really need to dedicate 130 or so minutes for a ho-hum end-of-year biopic with two theatre kids doing Mid-Atlantic accents when I could’ve watched two exciting movies from the 1930s in that time? But then we get to the genuinely demonic image of Bradley Cooper in Trash Humpers-esque old man prosthetics with his unbuttoned shirt cradling a twink and dancing under a harsh red light, all scored to “Shout” by Tears for Fears. Now sure to overtake Donnie Darko as the most iconic TFF needle drop, at least within this brief moment of screen time, I finally got a glimpse into the more interesting movie embedded within Cooper’s often belaboured prestige picture filmmaking (he’s still better than Ben Affleck though, as much as I prefer Ben the man). The takeaway from Maestro, after all, is that Cooper the movie star and artiste has some THOUGHTS on what it means to be a famous closeted man, certainly presumptuous on his end that we care that much. Trying to pull a “the movie was actually about his wife, really” move in the checkout line rings rather false, and one sees the better film in the one that shuns two forms of respectability politics, be it of awards movies or gay representation.

And, for the record, I really liked A Star is Born!

Ethan Vestby co-runs the Bleeding Edge Screening series in Toronto.

The Zone of Interest

by Gabrielle Marceau

The much talked about moment in The Zone of Interest (if you haven't seen it and plan to, I’d close this and go on with your day) when Auschwitz commandant, Rudolf Höss, walks through his office building, stops to vomit, and glances down the hall. The film cuts from its 1943 setting—and also its basic mode of storytelling—to scenes of cleaners making their way through modern Auschwitz, now a museum, windexing the display cases and vacuuming halls lined with piles of shoes and gold teeth. The scene, like the rest of the film, keeps us at a slight distance from what we know is there, just out of frame but, of course, not out of mind—the Holocaust is never very far out of mind, if by mind we mean our public imagination. When we cut back to Höss, we know he has seen what we have, some portal to the future opened up: history has condemned him.

But there is something else in this cut. The glass case of piled-up shoes looks, I’m almost loath to say, like a frame, delineated on four sides by the window pane, with a guttingly simple, deliberate aesthetic. (I think of the curator or historians placing the shoes, maybe attending to placement for maximum effect.) Any representation of the Holocaust, even the most bare-bones documentary, seemingly unobstructed by authorial style, has an aesthetic goal beyond what it is simply representing. We cannot escape that to make a film, a poem, or an exhibition about the Holocaust, is to aestheticize it. And as Adorno said, to turn our knowledge of horror into a thing (a poem or a film) is to distance ourselves from it. Glazer knows this, and he doesn’t let us get comfortable, even from the vantage point of being (in this case) on the right side of history.

I saw The Zone of Interest before the October 7th attacks that launched the brutal, genocidal siege on Gaza, but it’s impossible now to think of the film in any other way—to not think about another wall in another country that keeps atrocity on one side out of sight from the leisurely lives on the other. We can imagine what art will be made about Palestine one day, the film crews gathered on the Cannes Croisette, the land acknowledgements before cultural events, the rubble cased in museums. But looking back on it now, The Zone of Interest seems to say that there never really is a right side of history if we are so keen on repeating it.

Gabrielle Marceau is a writer and critic.

In the mood for something more?

Dive into the juicy archives of our newsletter and our online magazine.

Wondering what to watch?

Choose a mood on our Film Recommendation Generator and get a curated pick from writers, filmmakers, and poets.

Support us!

If you’d like to donate to our mag, here’s our PayPal! We’re volunteer-run, and donations go directly to our contributor honorariums and operating costs.