The Wonky Beauty of Shelley Duvall ✨

Aaditya Aggarwal's ode to New Hollywood’s kooky starlet. And don't forget to submit to Issue 11!

The Wonky Beauty of Shelley Duvall

New Hollywood’s Kooky Starlet

by Aaditya Aggarwal

“Beauty is pleasure regarded as the quality of a thing.”

—George Santayana, The Sense of Beauty

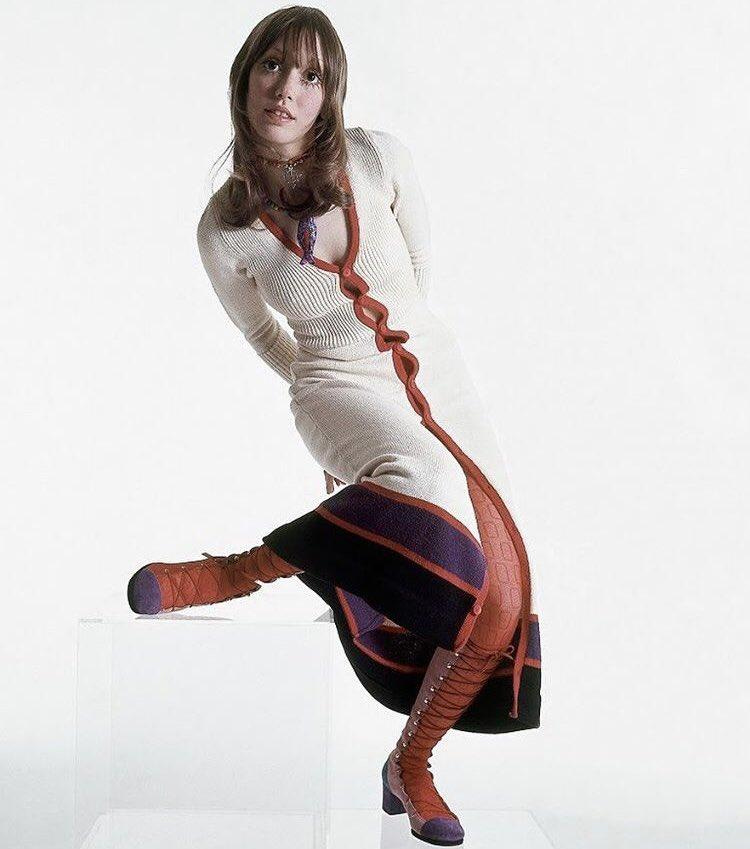

Texas Twiggy. Sparrowlegs. Chatty, Cartoony, Cathy. Nicknames, both adoring and abrasive, undeniably punctuate the story of her askew physicality. They wink at the poking unreadability and the goggling gaze of her. Manic Mouse. Raggedy Ann. Toothy Thumbelina. They conjure the mythical, sentient fauna in the gothic fairytales of the Brothers’ Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen that she would later come to enact in her self-produced children’s TV programme, Faerie Tale Theatre (1982-87). One gropes in the dark for her final, funereal title, attempting allusion, with cheek and bite, to her kooky stylisms.

But all monikers fail to capture the naively incandescent genius of Shelley Duvall.

This is a litany for Shelley: puzzlingly watchable, limby country-waif. Fixture in the musings of many a Tumblr girl. In recent years, reappraised recluse, aging, aloof, estranged, and now deceased. A litany, for the atypical movie star of the seventies. “The woman wrapped in a fairytale.” Unmissable muse to Robert Altman. Proto-manic-pixie-dream-girl of the pre-Reagan years. The one with a deft, taciturn, animacy. The one whose distinct daffiness is totemic, in a sense, to New American Cinema.

New Hollywood needed Shelley Duvall. Echoing the postwar malaise of a destructively imperialist, dwindling American empire, and coloured by the artistic influences of the French New Wave, Japanese New Wave and Italian Neorealism, the early years of New American Cinema relied on a varied cohort of “wonky” beauties to be cast as its new crop of leading ladies. The pre-Streep list of working actresses included formidable talents such as: unmatched triple threat and stage-to-film star Barbra Streisand; politically surveilled and performatively dynamic Jane “Hanoi” Fonda; loony and languid Jessica Lange; musically gifted and acrobatic Liza Minelli; ardently precise with a surreptitious intensity, Cicely Tyson; deft, discerning, and glamorous Pam Grier; simmeringly detailed Ellen Burstyn; television-to-film, complex everywomen, Sally Field and Mary Tyler Moore; archetypally quirky and urbane Diane Keaton; and sharp-edged, cautiously brilliant, Faye Dunaway.

Among these screen-engorging belles, Duvall was comfortably off-kilter, knottily alt, troubling the distinctions of beautiful and unbeautiful. She alerted us to the beatific in the unvarnished, her spindly frame belying a lustrous too-muchness. Be it Altman, Kubrick, or Warhol, the maverick auteur-type harboured a deep fascination for the curious ingenue. Complementing studio film’s renewed regard for the discarded and disenfranchised, Duvall’s screen persona offered us an off-beat identification with codes of the onlooker, the urchin, the striver, the townie. She effectively communicated an unrehearsed expertise, of being a puzzle piece, of being a slyly guileless foil, of being looked at.

BREWSTER MCCLOUD (1970)

Born in 1949, Shelley Duvall actualized an antithesis of the Southern Belle. The South Junior Texas College dropout (“I didn’t like vivisection”) was an aspiring scientist when she was first sighted by Altman’s talent scout at her painter-boyfriend’s house party. Altman’s hybrid genre caper Brewster Mccloud (1970) introduced Duvall to the national cinemagoer as flirtatious Astrodome tour guide Suzanne Davis. In her acting debut, she ascertained a raw finesse, maneuvering the film’s protagonist in a route with teasing inquisition. Wielding a wet mullet, with a bullhorn in hand, it was her saucer eyes that piqued curiosity. A thick Southern drawl—her swiveling, cuckoo lilt with an untouched and fluvial cadence—cemented it. Batting her Venus Flytrap-petalled eyelashes, she recalled avant-garde British model Twiggy. “Are you trying to steal my car?” Duvall’s Suzanne remarks with a childlike politesse to Bud Cort’s introverted teenaged Brewster. “I asked if you’re trying to steal my car?” She coquettes, still unserious, or perhaps matter-of-fact, steering this meet-cute while Brewster steers the wheel.

NASHVILLE (1975)

The echoes of her gullible but conspiring screen manner later surfaced in her cameo as Martha a.k.a L.A. Joan, Californian groupie with “an indiscriminate appetite for male musicians,” in Altman’s country opus Nashville (1975). Dressed in bralettes and crop tops with booty shorts, long skirts, loose berets, and headscarves to match, Duvall’s L.A. Joan felt meanderingly excitable, with a risky wonder, desirously flitting, “always searching for a new man to be with.”

The Altman protégé later commended the director for her weightless yet affecting turns: “He encouraged me to be myself on the screen, to never take acting lessons, or to take myself too seriously. When I play a character, at that moment nothing else exists.”

3 WOMEN (1977)

Over the course of this decade, Altman would cast Duvall in seven of his films in a range of roles with varying screen times. The director-actress duo creatively peaked in Duvall’s staggering turn as Millie Lamoureux in 3 Women (1977). A first among Duvall’s modestly numbered leading lady turns, Millie came to Altman in a dream, and culminated in a Best Actress win for Duvall at the 1977 Cannes Film Festival. One of arguably three protagonists of the film, Millie is a warmly braggadocious, head-in-the-clouds worker at a geriatric physical recovery center in a remote desert town in California. “Frivolous Cosmo girl,” critic Andrew Sarris terms the character in his review for the Village Voice, praising Duvall’s “curiously affecting meticulousness.” Duvall vocalizes Millie's magazine-informed ramblings, shapeshifting—pink, pastel, printed, poppy—into the white noise that surrounds her apathetic colleagues. “Say, would you check my glands for me? My neck glands.” Duvall casually asks a fellow care home assistant at lunch. “They’ve been swollen for weeks,” she remarks, her bodily admonitions as humorously even-toned as her party-hosting tips, mentioned unsolicited to peers.

“They’re my favourite colours,” Duvall’s Millie similarly waxes about yellows and purples to Pinky, the younger hire and soon-to-be complicated companion, essayed by an equally spellbinding Sissy Spacek. Altman’s impressionistic drama entangles the two heroines in a conflicting but codependent kinship, their crises of identity recalling the power struggles between archetypal ingenue and dame in All About Eve (1950), or even the sapphic merging and mirroring of selves in Persona (1966). “Like irises,” Duvall’s Millie continues, squinting at the road in a midday daze, assured in the hold of her rosy delusions to a dazzled Pinky. “I love irises. And flowers. And candlelight. They’re so romantic.”

Seven years into a burgeoning Hollywood career, Duvall’s musical drawl had now assumed an unmistakable signature in 3 Women. Unlike past performances, her depth of onscreen delirium as Millie gorgeously undid the star’s own typecast trappings of wide-eyed mania. Now more than ever, Duvall was participatory and active. She reportedly co-authored Millie with Altman, using her diary entries, on-the-fly notations, and improvisations to add shading and texture to Millie's entanglements. In a later interview, Altman synthesizes her easy prowess: “Shelley allowed the fool in her to show itself, what I call the ‘pink stuff,’ what you normally don’t show people. Real actors show the ‘pink stuff.’”

THIEVES LIKE US (1974)

Following her movingly wordless and brief role as mute widow-turned-sex worker Ida in Altman’s revisionist Western McCabe And Mrs. Miller (1971), Duvall was the leading lady of the director’s next period outing, an anti-heroic take on Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Thieves Like Us (1974). In an affecting turn, she essayed the fatigued but hopeful Depression-era country-girl-next-door and garageman’s daughter Keechie, who gets romantically involved with thieving robber Bowie (Keith Carradine).

“I don’t even breathe it in,” Duvall’s Keechie claims when Bowie asks about her smoking habit. The actress looks at her lover with a sedate focus while slivering circles of nicotine emanate from her mouth. Critic Roger Ebert once noted her gesture, “slowly exhaling little plumes of smoke,” its rooted finesse eschewing the makings of a cigarette-smoking femme fatale.

One can argue that it is in Thieves Like Us that Duvall’s naturalist sway triumphs. “You look awful,” she accents, nonchalant and nimble, cajoling, mid-courtship. Later, post-altercation, she presses Bowie’s shoulders, cushions her chin into the crook of his neck, gazing at him with plain surrender, “I’m already mixed up with you.” An achingly doomed sincerity pronounces her delivery. “Nothing is said,” as Ebert comments. And so much is.

BERNICE BOBS HER HAIR (1976)

Canvassing a cherubic stoicism, the affectations of Duvall rarely sought centre stage, but they always found one. Her performative ingenuity soars in the underseen Bernice Bobs Her Hair (1976). In her rare outing as top-billed lead directed by Joan Micklin Silver, the actress starred as the titular Bernice, more oddball debutante than unqualified wallflower, who turns to her charming socialite cousin Marjorie for advice in order to be more socially desirable. A drab entry into Marjorie’s social circles, Duvall’s Bernice playfully relishes in judging, then leaning into, both the gawk and the glamour of Depression-era Saturday night dances. “Mr. Charlie Paulson, do you think I ought to have my hair bobbed?” she asks a male party guest. In her first earnest attempt at proper flirtation within the film, Duvall nails the bifurcated tonality of this comedy of manners. Her makeover arc extends social allegory, bearing a strange, stylistic likeness to the “rags-to-riches,” silent-to-talkies heroines, like Joan Crawford as a flapper in Our Dancing Daughters (1928) and as a mistress in Possessed (1947).

POPEYE (1980)

After filming her painstakingly arresting performance as Wendy Torrance in The Shining (1980), Duvall’s spontaneous and unburdened singularity gleamed, vaporous and adroit, in her ambiguously toned and astonishingly complex portrayal of swan-necked and thin-limbed Olive Oyl in Altman’s musical dramedy Popeye (1980). “Possibly she can do this so simply because she accepts herself as a cartoon to start with, and, working from that, goes way past it,” renowned critic Pauline Kael marvelled at Duvall’s humorous pathos, her “sense of hopelessness,” causing you to “feel a catch in your throat while you’re smiling.”

At her peak, Altman’s rangy muse managed to inspire opposing tensions, both an untraceability and an approachability, for a spectator to pick apart, sliver through, step into. Ebert credits his fondness for the late Southern dame to her distinctly unbridled “openness” within a scene. It’s almost as if, he notes, “nothing has come between her open face and our eyes—no camera, dialogue, makeup, method of acting—and she is just spontaneously being the character.” Her ovular mien emanated an uncanny cool, not in spite but, by virtue of her popping glances. Not unlike the startling Spanish supermodel Rossy de Palma, transiting Almodóvar’s rougely roguish melodramas, the cubist materiality of Duvall’s visage was akin to Carol Donnell, Leone Lane, or Sandy Dennis, whose faces revealed the juts and knots of the peripheral American, of the bumbling outcast, the jester, the vagabond, the runaway, the daughter. This jolie-laide demands, on occasion, with unwitting flagrance, modelesque captures on the pages of Vogue and Interview. “A wonky beauty,” as Chloë Sevigny calls herself in her recent interview with Elle, against the long-anointed It-Girl’s mother’s more refined, “classical beauty.” The wonky beauty’s viscerocranium may boast a lopsided nose, agape mouth, downturned lip, buck-toothed overbite, crooked smile, or freckled visage. Twisting, contorting, longitudinal, she claims distinction.

Rougher around the edges, delectably alienic, bony, au-naturel, the wonky beauty is bisyllabic, as is Shelley Duvall. Quizzical creature, “of long neck and string-bean body and the clodhoppers,” Kael once observed, anointing Duvall “a high-fashion beauty” in the same breath. All of Duvall’s textured edges, pointy asymmetries, oddly quotidian humanness, editorial wilderness, are the very foundation of her woozy, uncanonized, desirability, that sought-after but unfounded, movie star appeal. “But beauty was never her intention or her project,” retorts novelist Nicole Flattery in her tribute to the actress in The Financial Times. And still, you just can’t stop looking at her. Nor will your eyes ever stop finding her: our bluish, bobbing, moony-toony, agog, androgyne. Lone starlet of the Lone Star State, or some might say, “the quintessential American actress.”

Aaditya Aggarwal is a writer, researcher, and film curator. Twitter: stelladilli

Last Call for Issue 11 Submissions 📣

You only have two more days to submit to Issue 11: Period Piece! Send us your submissions by August 31st—our complete guidelines are below:

In the mood for something more?

Dive into the juicy archives of our newsletter and our online magazine.

Wondering what to watch?

Choose a mood on our Film Recommendation Generator and get a curated pick from writers, filmmakers, and poets.

Support us!

If you’d like to donate to our mag, here’s our PayPal! We’re volunteer-run, and donations go directly to our contributor honorariums and operating costs.

🤩 what a piece!!